Breadcrumb

A rare disease researcher at Mizzou stepped out of the lab and into the role of a clinical trial participant, an experience that gave her a fresh perspective on the process and a deeper appreciation for the human side of science.

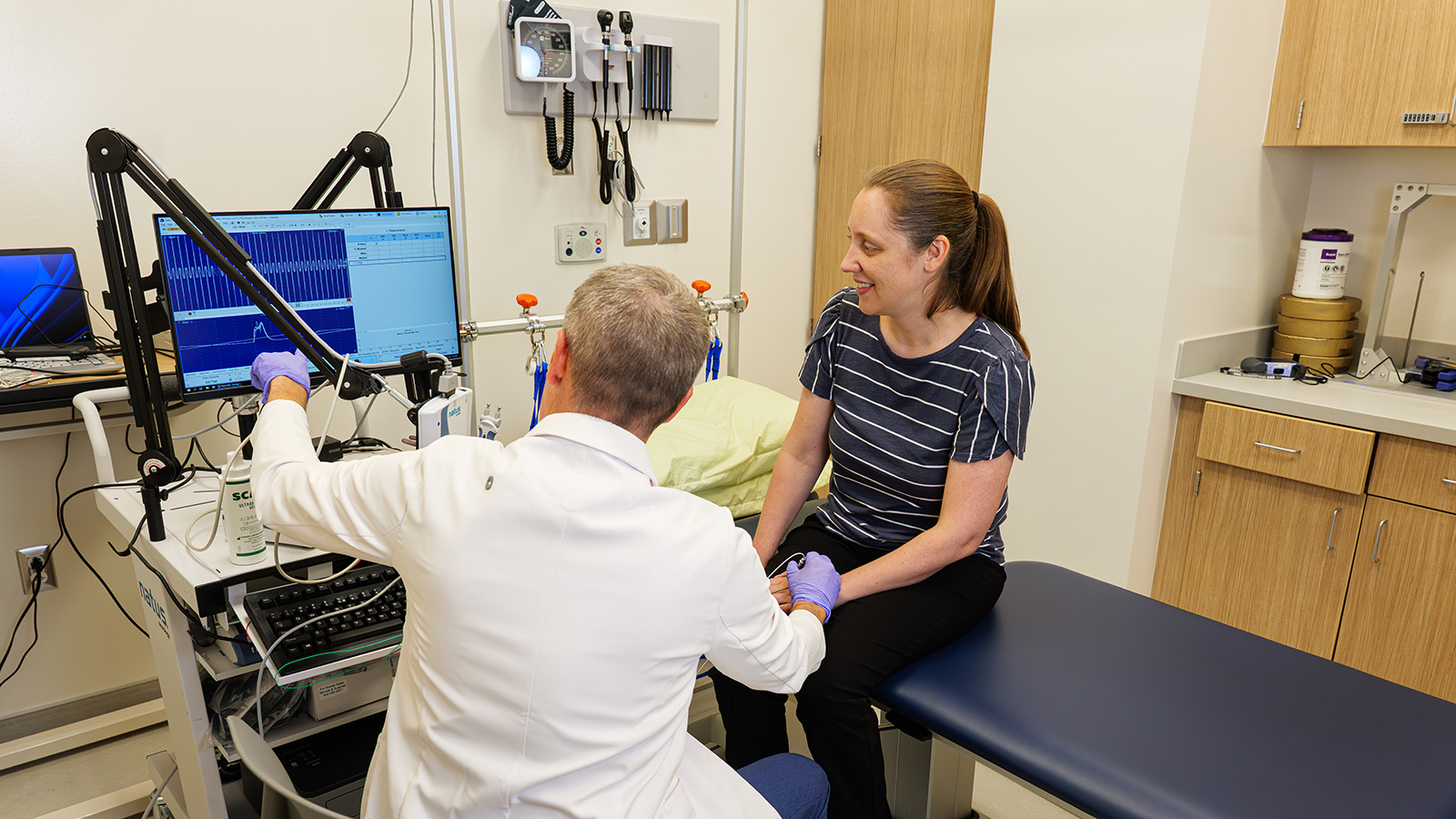

MU Health Care physician and NextGen Precision Health researcher Ryan Castoro administers assessments with Kathryn Moss in an exam room at the Clinical and Translational Science Unit.

June 2, 2025

By Harper Snyder

A diagnosis of Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease ingrained a scientific curiosity in the young Kathryn Moss. CMT is a rare inherited neuromuscular disorder affecting the peripheral nervous system, with symptoms like muscle weakness and sensory abnormalities in the legs and sometimes arms. In high school, she decided to pursue a career in science to better understand the mechanisms underlying her diagnosis, without knowing what exactly the path would look like. Her journey ultimately led her to Mizzou, where she is now a NextGen Precision Health researcher and an assistant professor of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. She focuses on the basic cellular and molecular science underlying our understanding of CMT to dig deeper into past findings and bridge gaps in the field. “Understanding what causes CMT helps us make smarter choices about how to treat it,” Moss explains.

Her efforts to investigate CMT do not stop at her own lab bench. She uses her status as a CMT patient to support other scientists in their search for answers by participating in clinical trials. “I’m strongly committed to supporting therapeutic discovery for CMT,” says Moss. This dual perspective – one as both a scientist and a clinical trial participant – leaves Moss with the rare opportunity to both collect data and contribute to it.

So what’s happening in the CMT field?

There’s been a lot of momentum in recent years with new therapies coming down the pipeline for CMT, but this will likely be an iterative process, where each therapeutic success builds the foundation for new and improved treatments that lead to better outcomes for patients. This is where my research fits in. I want to understand basic mechanisms of disease so we can use that information to improve therapies. When it comes to gene therapy development, basic science is often undervalued. People often believe you simply need to fix the gene; however, science is more complex than that, biology is more complex than that.

How has your personal diagnosis of CMT impacted your scientific trajectory?

It’s been my driving force. I decided to research CMT in high school because I wanted to understand my own condition. I had no clue what that meant at the time, but regardless, it was my goal and it has finally become a reality. As my symptoms progressed, so did my motivation—especially since lab work can be physically demanding. It’s a catch-22: the work exacerbates my pain, but it also fuels my resolve to find solutions.

|  |

What clinical trial did you participate in?

For CMT patients, this drug is aimed at improving the function of the neuromuscular junction, which is where the nervous system connects to the muscle. Since my subtype (CMT1A) involves myelin sheath damage, the drug wouldn’t repair that, but it could enhance remaining nerve-muscle communication. Ideally, it might work best as part of a combination therapy.

What was it like?

My participation in the clinical trial took exactly six weeks from start to finish. There were three weeks of treatment, preceded by screening and baseline tests. Participants received either drug or placebo, and although I knew it would be a blinded experimental protocol, it was interesting that even the coordinators didn’t know who received what. Only the pharmacy had access to that. Some of the testing we underwent during our visits included the six-minute walk test, balance assessments, and strength measurements. I found the six-minute walk test to be harder than I expected, and the dorsiflexion in the strength measurements were nearly impossible. It was definitely more tiring than I anticipated and that’s coming from someone who works in the same building! All that I had to do was travel from the fourth floor to the third floor for every appointment, but others would most likely have to take the full day off of work to account for travel. Still, clinical trials are essential for developing new and better treatments, so the time and effort were absolutely worth the investment.

|

How did your dual role as researcher and participant shape your experience?

Honestly, I felt like I would know a little more about the process, but it turned out I didn’t know much. I’d heard of all the tests and outcome measures used to track symptom progression in CMT, but I had never done them. Firstly, it highlighted the rigor of clinical trials and the importance of patient recruitment. In support of that rigor, this trial excluded patients who use leg braces (a common support), which shrank an already small pool of rare disease patients. Secondly, it emphasized the critical inclusion of patient perspectives in translational research. CMT conferences are one place in which scientists and clinicians are able to hear directly from patients about their symptoms, which can be incredibly helpful in identifying understudied areas. For example, vestibular dysfunction or hearing loss aren’t part of standard diagnostics, but they’re common patient experiences.

Overall, this was a good reminder to keep the end goal in sight: treatments that actually help patients. I don’t want to get so caught up in, say, what a single protein does that I lose sight of the bigger goal. Additionally, I was inspired to dream. My research could end up in a clinical trial someday, potentially right here at the NextGen CTSU. It would be incredibly rewarding to see research from my lab directly translated into therapies that benefit patients.

Is there a piece of advice you would give to other researchers?

Participate in trials yourself! Consider participating in clinical trials, even as a healthy control. It’s a powerful way to support research and build an appreciation of what patients experience. For rare diseases, every participant enrollment counts. We must make trials accessible—maybe consider bundling multiple studies into one visit to reduce the burden to participants.